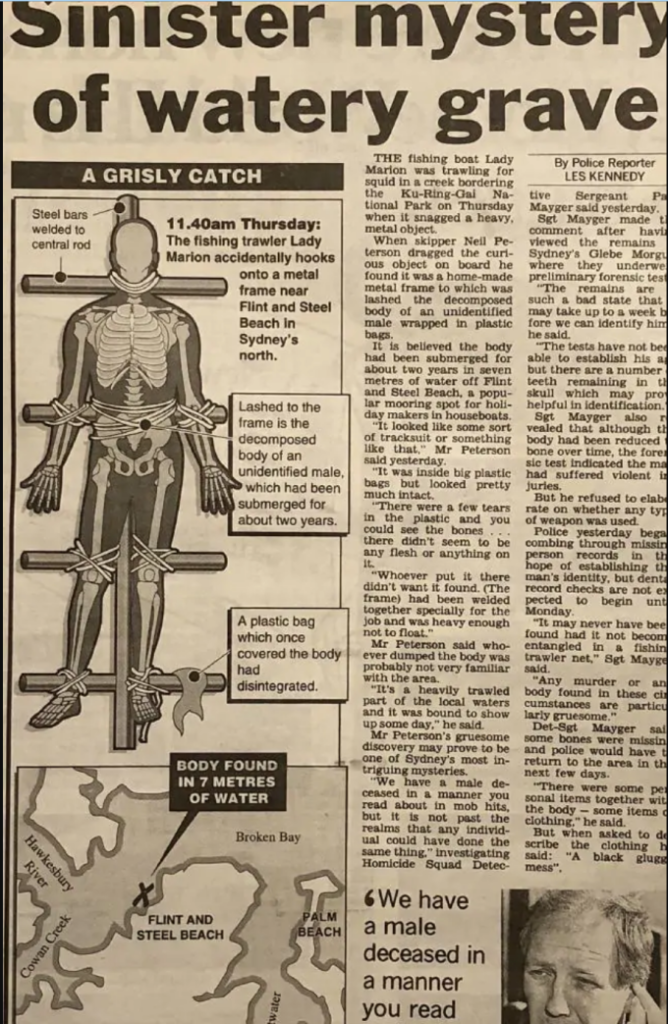

In the early hours of August 11 1994, the crew of the Lady Marion were trawling the peaceful waters of the Hawkesbury River north of Sydney looking for prawns, when captain Mark Peterson felt an almighty tug in his net – but his catch wasn’t the nice big haul he was hoping for. Instead, what was caught in his net was a metal cross covered in plastic bags — and under those bags were the decaying remains of a human body, tied to the cross with wires.

Police were called immediately, but since the body had been submerged for some time (a least a year, by the coroner’s estimation) it was difficult to collect any forensic evidence. The coroner could tell it was the body of a man, a rather diminutive one at that (around 165cm), who had dark hair and may have been of Mediterranean heritage, and aged between 20 and 45 years old.

It was almost as if the man had gone out of his way to be unidentifiable — or somebody had taken pains to ensure this was the case. He had no personal belongings on him, save for a packet of cigarettes and a lighter. His clothing was unmarked and mass-produced: an “Everything Australia” polo shirt and “No Sweat” trackpants, both sized medium.

Forensic anthropologists worked with the man’s bone structure to create a facial reconstruction for police to circulate, and once that was made public, many members of the public came forward with possible identifications of the man, who became known as “Rack Man” thanks to the metal contraption he was found strapped to.

What was clear, though, was this was a deliberate and meticulous killing. The steel-framed crucifix was custom-built for the unidentified man. The welding was professional and concise, and the cross-frame matched the man’s outstretched arma perfectly. It was also far too heavy for a single person to have lifted and dumped into the river, suggesting more than one perpetrator.

Leads provided by the public saw police investigate a number of shady missing persons: convicted drug dealer Joe Biviano from the Sydney suburb of Drummoyne; Kings Cross businessman Peter Mitris and Chris Dale Flannery, known to underworld figures as “Mr. Renta-Kill”. All these leads were dismissed due to discrepancies in height, dental records and other identifying factors. A reward for information on who was the “Rack Man” was increased over time until it hit $100,000. With no clues as to his real identity, the “Rack Man” lay refrigerated in an inner-Sydney morgue for 25 years.

Then a breakthrough occurred. DNA testing led to the “Rack Man” being identified as 37 year old Max Tancevski, who had disappeared from Sydney in January 1993, and who had been considered as a possible suspect.

DNA technology in the mid-1990’s was not advanced enough to make a positive identification. Tancevski was known to be a heavy gambler – had he borrowed money to fund his gambling and was unable to pay back his debt? The unusual method of killing and/or disposing of the body was excessive, and is unlikely to be a random attack carried out by a stranger. This sort of crime scene is more concurrent with gang related violence, done with the intent of sending a message to warn others not to cross the killers again.

Police had no idea who committed the murder, but information was passed on to the NSW cold case homicide squad to investigate further. As of July 2022, the identity of the person(s) who murdered Tancevski are still unknown.

Justine Ford’s book “Unsolved Australia – Who Was the Rack Man?” Macmillan Publishing, Sydney 2015, pp.115-123 was used as the main source for this blog post.