Late on the afternoon of Sunday, the 10th of October 1880, farm worker William Johnston was riding his horse at Mutton Fish Point, near the coastal New South Wales town of Bermagui, 100 kilometres south of Sydney, when he noticed something ‘shining’ on the rocks. He dismounted, tied his horse to a tree and walked closer, discovering that the ‘shining’ object was a fishing boat, painted green with its mast and sail lashed.

In his subsequent statutory declaration Johnston wrote:

I went over to the boat and judged from her position that she had been wrecked. I did not touch or in any way interfere with anything…..I returned to my horse and only noticed my own tracks going out to the boat. I mounted my horse and rode away. After going about 100 yards [90 metres] it struck me to look at my watch, saying to myself, ‘as this is likely to have been a drowning match they will want to know the time I found the boat’. I saw that it was about 4.20 pm.

Johnston galloped to a nearby property owned by dairy farmer Albert Read. Both men returned to the boat and inspected it more closely. It was obvious to them that the vessel had been deliberately damaged. Someone had dumped a pile of boulders, along with pillows, blankets and piles of clothing into the stern. Read reached down and retrieved a book. It was a geology text, and written in copperplate on the flyleaf was the name ‘Lamont Young’.

Tall, bearded Lamont Henry Young was a 29 year old geological surveyor with the NSW Department of Mines. He was highly thought of by his colleagues, both for his considerable expertise and his modest demeanour. In October 1880 Lamont’s superiors instructed him to survey the newly-discovered goldfields north of Bermagui with a field assistant named Maximilan Schneider, who had recently arrived from Germany. Young and Schneider reached the goldfields on the 8th of October, and after pitching their tent, introduced themselves to Senior Constable John Berry, officer in charge of the police camp at the diggings. The three men lunched together, and then Schneider excused himself, saying that he was returning to the tent. He was never seen again.

Young spent the rest of the day examining the goldfields, and accepted an invitation from Berry to go fishing the next day. Young started the long walk back to his camp. Peter Egstrom, owner of a sly grog store, noticed Young near the local lagoon, walking towards Bermagui Heads. He a miner named Henderson spotted him again, shortly afterwards – the last time anyone was known to have seen Young, alive or dead.

On the morning of the 11th of October, Berry and Read, accompanied by goldfields warden Henry Keightley, examined the abandoned fishing boat. A second book signed by Young was found among the garbage. Why had Young been aboard the vessel? Who were his companions? And more to the point, where were all of them now?

Keightley noticed that someone had vomited copiously in the stern. Feeling sick, he ordered Berry to continue the examination of the boat. Berry produced a minutely detailed inventory of the boat’s contents, which included a pocket compass, several sacks of potatoes and pipe and coat belonging to Schneider, the other missing man.

Police determined that the boat belonged to a Thomas Towers, who two days earlier had set sail from his home at Bateman’s Bay, approximately 100 kilometres up the coast. He and his companions William Lloyd and Daniel Casey had intended to fish off Bermagui, and sell their catch, along with the sacks of potatoes to the goldminers.

In a report to his superiors, Keightley stated that there was nothing to suggest that anything of a unusual nature had taken place on board. There were no blood marks nor any sign of a struggle. A bullet had been found in the boat, but it had been used as a sinker for a fishing line. Senior Constable Berry was unable to continue the investigation, as he fell ill with a fever and vomiting. When he returned to duty nine days later he was told that the remains of a campfire and meal had been found close to the wrecked boat.

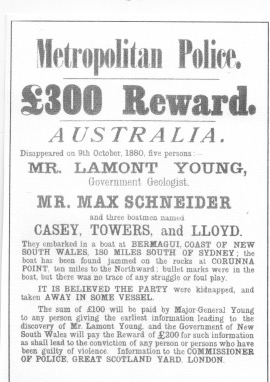

Keightley offered a reward of 10 pounds for the recovery of Young’s body, while the Metropolitan Police in London offered a 300 pound reward for information relating Young, Schneider and the boatmen Casey, Towers and Lloyd. Police, Mines Department staff and volunteers conducted an extensive land and see search for the five missing men – but found nothing.

A journalist writing in the Sydney Morning Herald described the whole affair as ‘a puzzle enshrouded in an enigma’ – adding,

‘I cannot conceive of any motive to account for the horrible suspicion that they were murdered …. But how could the murders (assuming they existed) have known where the men were to land – unless they were murdered by the first party they met? …. The idea is so dreadful and the motive so unintelligible that I cannot yet entertain it.”

Young’s father Major General CB Young wrote to the NSW Under-Secretary of Mines on the 31st of December:

‘The universal conclusion of all parties in this country is that the five men could not have drowned or been murdered without leaving some trace behind. I earnestly beg of you, my dear sir …. to take up this line, to see what the Governments, Imperial and local, have done in this direction, to look for the bodies.”

Young also raised suspicions about Schneider, his son’s assistant:

What sort of person and of what character was Mr Schneider? Where does he come from in Germany and to whom was he known in England?”

With the official searches and investigations appearing to have run into a brick wall, members of the public weighed in with their own investigations, searches and theories as to how the five men had disappeared. One man, William Tait, visited police headquarters and claimed that Lamont Young had spoken to him on the 13th of November, more than a month after the disappearance. Tait, a self-styled spiritualist, claimed that Young had appeared to him as a ghost, and revealed that he and his companions were murdered by three men who asked them for matches to light their pipes. After beating the five victims to death with oars, the killers buried the bodies in a deep hole near a black stump, about 50 metres above the high water mark, covering the makeshift grave with boulders. Police mounted a search, but found no black stump nor a cairn of boulders.

More promising to detectives was a small blue bottle, filled with a mysterious liquid, recovered from a saddlebag in the boat. There was speculation that the liquid may have been an exotic poison, but tests shows that it was the balm, oil of copaiva.

On the 11th of March 1885 the Melbourne Argus reported that Young’s bloodstained coat, ridden with bullet holes, had been found near Bermagui. Unfortunately for the Argus, the ‘report’ was a practical joke, and the paper was forced to make an embarrassing retraction.

On the 22nd of August 1888 the Bega Gazette announced that it had uncovered vital new evidence:

Though the police authorities have kept the matter a secret, it has transpired that during the past two months the police have had under surveillance a person suspected of complicity in the Bermagui murder, but that he has escaped their clutches. It appears that some time ago a man who is said to have lived with a woman near the scene of the alleged murder, came to Sydney and married a barmaid employed in one of the leading hotels. Shortly after their marriage, he gave way to drink and on several occasions uttered remarks which led his wife to believe he was concerned in the murder of Lamont Young and his companions. The detective police got wind of the affair and kept the suspect person under surveillance for several days. All at once, however he disappeared …. The barmaid has since returned to her situation in the hotel from which she was married and expresses herself as willing to aid the authorities in bringing the supposed murderer to the police.

Bega police checked with their colleagues in Sydney. There was no barmaid, nor a drunken husband who had confessed to the murder – just the writings of an imaginative journalist.

To this day, there is still no definitive proof of what happened to the five men, not has there been a credible explanation found for the abandoned boat and its contents. The inlet where the boat was found was renamed Mystery Bay. A park and road is named after Lamont Young, while a monument was erected in 1980 to commemorate what is still one of the most mysterious and unexplained disappearances in Australian history.

The source for this blog post is “The Five Missing Men of Bermagui”, by John Pinkney, from his book “Unsolved – Unexplained – Unknown: Great Australian Mysteries”, Five Mile Press, Rowville Vic, 2004, pp. 269-281.

UPDATE: I have been in contact with Simon Smith, who has been researching the case for the past 20 or so years, building up an extensive collection of documents. He is currently writing a script based on the disappearances, with the main character being Lamont Young’s son (Naval Lieutenant Charles Young), who attempts to find out the reason for his father’s disappearance.